April 2009

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

A Summer Shower in the Magic Garden

1954-1959

Gelatin silver print

Further to the last post I have collected some images from the Czech photographer Josef Sudek (1896-1976), one of my favourite photographers. The images of this master photographer are a delight. Like the photographs of Eugene Atget they evince generosity in the understanding of light, space and humanity. Insightful writing on Josef Sudek by Charles Sawyer is included in the post.

Marcus

.

Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Everything around us, dead or alive, in the eyes of a crazy photographer mysteriously takes on many variations, so that a seemingly dead object comes to life through light or by its surroundings. And if the photographer has a bit of sense in his head maybe he is able to capture some of this – and I suppose that’s lyricism.”

“I believe a lot in instinct. One should never dull it by wanting to know everything. One shouldn’t ask too many questions but do what one does properly, never rush, and never torment oneself.”

“It would have bored me extremely to have restricted myself to one specific direction for my whole life, for example, landscape photography. A photographer should never impose such restrictions upon himself.”

.

Josef Sudek

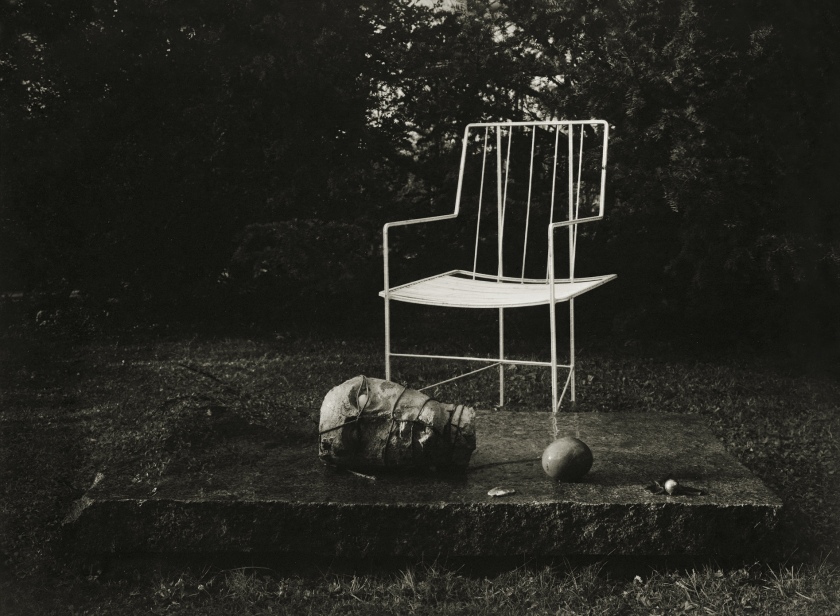

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

In the enchanted garden

1954-1959

From the series Remembrances

Gelatin silver print

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Untitled

1967

Gelatin silver print

“The systematic approach, and the dogged aesthetic experimentation of Sudek are akin to the working habits of Cezanne. But these alone are insufficient to make great art or even good art. On the contrary, if these are all one sees in a work, then the cumulative burden of so much plain labor would be unbearable. Sudek’s devotion to work may have integrated his shattered life but it could not have offered him the spiritual redemption he was seeking; only his aesthetic quest could bring this. It is the struggle for spiritual redemption through his aesthetic quest that gives Sudek’s best photographs their true power. Two qualities characterise his best work: a rich diversity of light values in the low end of the tonal scale, and the representation of light as a substance occupying its own space. The former, the diversity of light values, requires very delicate treatment of the materials, especially the negative, but also the paper (Sudek used silver halide papers in the main). The latter, the portrayal of light as substance, is a more original trait than his tonal palette, which one sees in occasional prints of other photographers. Flaubert once expressed an ambition to write a book which would have no subject, “a book dependent on nothing external … held together by the strength of its style.” Photographers have sometimes expressed parallel aspirations to make light itself the subject of their photographs, leaving the banal, material world behind. Both ideals are, of course, unobtainable, but nonetheless they may be worth pursuing. (Artists, in their pursuit of the unobtainable, are not so likely to be called pathological as others, of us, though recent developments in the philosophy of science tend to view the scientist’s quest for truth as equally quixotic).

Sudek has come closer than any other photographer to catching this illusive goal. His devices for this effect are simple and highly poetic: the dust he raised in a frenzy when the light was just right, a gossamer curtain draped over a chair back, the mist from a garden sprinkler, even the ambient moisture in the atmosphere when the air is near dew point. The eye is usually accustomed to seeing not light but the surfaces it defines; when light is reflected from amorphous materials, however, perception of materiality shifts to light itself. Sudek looked for such materials everywhere. And then he usually balanced the ethereal luminescence with the contra-bass of his deep shadow tonalities. The effect is enchanting, and strongly conveys the human element which is the true content of his photographs. For, throughout all his photography, there is one dominant mood, one consistent viewpoint, and one overriding philosophy. The mood is melancholy and the point of view is romanticism. And overriding all this is a philosophic detachment, an attitude he shares with Spinoza. The attitude of detachment that characterises Sudek’s art accounts for both its strength and weakness: the strength which lies in the ideal of utter tranquility and the weakness which is found in the paucity of human intimacy. Some commentators find Sudek’s photos mysterious but I think this is a mistake: the air of mystery vanishes once we see in Sudek’s photography a person’s private salvation from despair.”

Charles Sawyer. “Josef Sudek” in Creative Camera April 1980, Number 190 [Online] Cited 14/04/2009 (no longer available online)

A good collection of Josef Sudek photographs can be found on the Museum of Fine Arts Boston website. Go to the site and enter ‘Josef Sudek’ in the Collection Search box to the right and then click on the arrow.

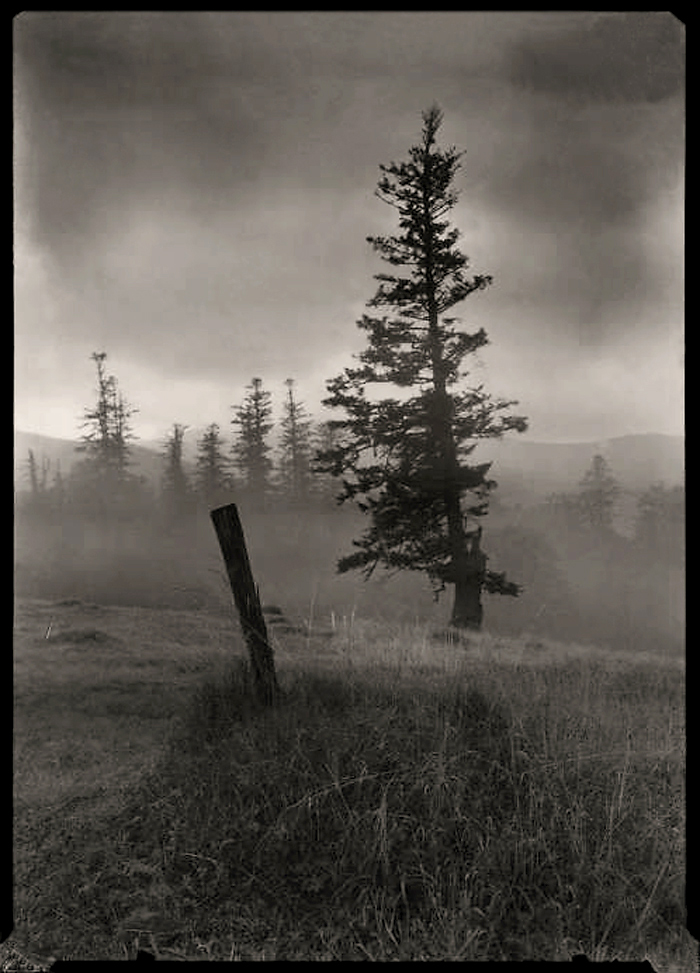

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

From the series Vanished Statues in Mionsi

1969

Gelatin silver print

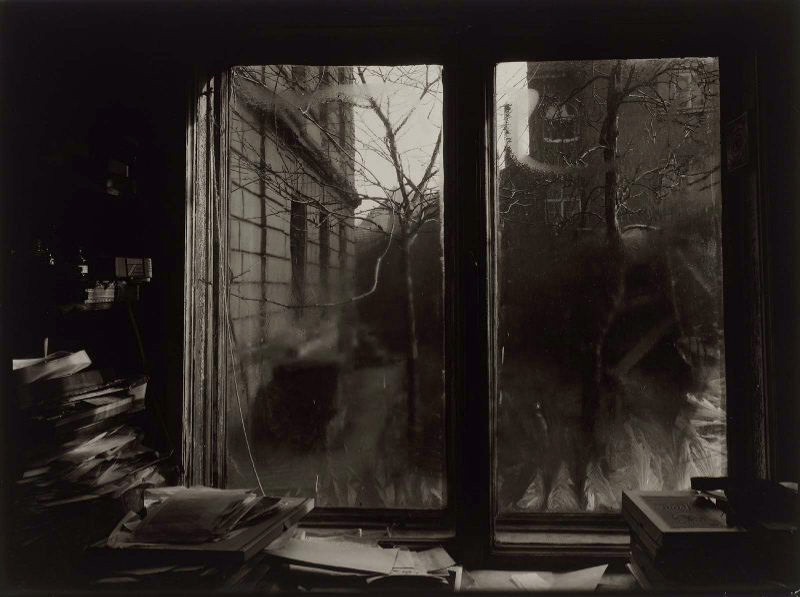

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

The Window of My Atelier

1969

Gelatin silver print

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Still-life after Caravaggio, Variation No 2 (or a night-time Variation)

1956

Gelatin silver print

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Still (Still Life According to Caravaggio)

1956

Gelatin silver print

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Remembrance of Mr. Magician (the garden of architect Rothmayer)

1959

Gelatin silver print

Otto Rothmayer (architect)

Otto Rothmayer was born during 1892 into a family of carpenters. He took up that trade, following in his father’s footsteps. Rothmayer studied at the Academy of Applied Arts in Prague under Jože Plečník’s guidance, and the Slovenian architect would inspire Rothmayer throughout his entire life. In fact, the design of the Rothmayer Villa was greatly influenced by Plečník’s Villa Stadion in Ljubljana. Rothmayer’s skill at carpentry came in handy as he designed much furniture. He made furniture for the gurus of Czech Cubism, architects Pavel Janák and Josef Gočár. Furniture he designed that does not fall under the category of Cubism but is rather simple and practical can be found in his villa and garden, for instance. His white chairs forged from rough steel were a big hit.

Work at Prague Castle

Plečník would not only be Rothmayer’s mentor but also his colleague. Rothmayer started working as Plečník’s assistant architect at Prague Castle in 1921, when Tomáš G. Masaryk was president of a young, democratic Czechoslovakia. Rothmayer even built a spiral staircase at Prague Castle, using what was then a new material – faux marble. When Plečník left his Castle post after 1930, Rothmayer continued to draw plans for the Castle until his retirement in 1958.

Other projects and the academic world

Rothmayer’s résumé does not only include his tenure at Prague Castle. He took up other projects, too. For instance, he designed three family houses and a side altar for a church in the Vinohrady district of Prague. He also designed museum exhibitions. Rothmayer went into teaching as well. He held the post of Professor of Interior Design at Prague’s Academy of Applied Arts in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when he left for political reasons. Rothmayer also was friends with photographer Josef Sudek, who took many snapshots at Otto’s Břevnov residence. Sudek’s photos set in the villa’s garden are particularly impressive. Otto Rothmayer died in 1966.

Tracy A. Burns. “The Rothmayer Villa: A gem of modern architecture,” on the Private Prague Guide website [Online] Cited 11/01/2019

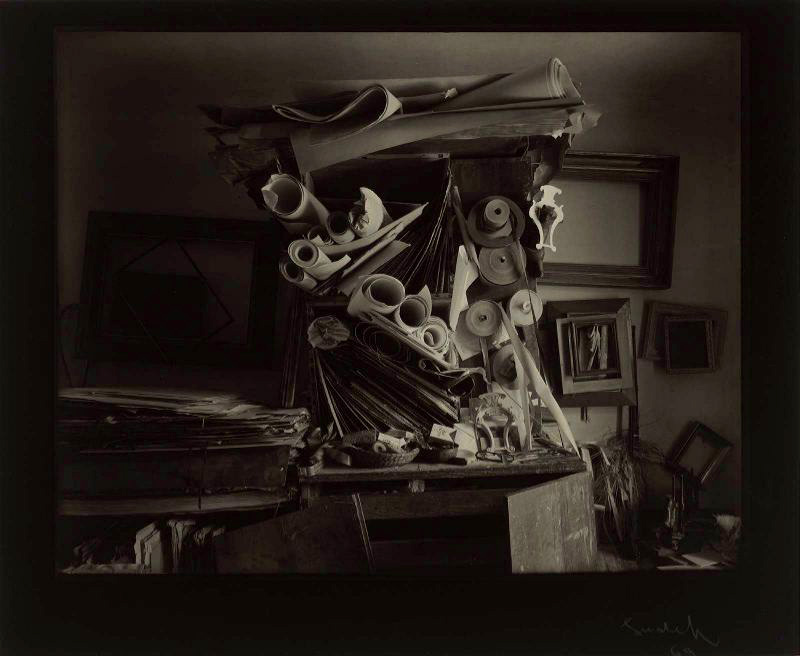

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Labyrinths

1969

Gelatin silver print

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Labyrinth of Spring

1968

Gelatin silver print

22.5 × 28.7cm (8 7/8 × 11 1/4 in)

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Remembrances of Architect Rothmayer, Mr. Magician

1960

Gelatin silver print

Sudek captured all what we would like to. His capture of light and reflection was wonderful and serves as a model for any aspiring photographer. I could never get bored looking at his work.

His use of shadow & light has inspired me. ❤